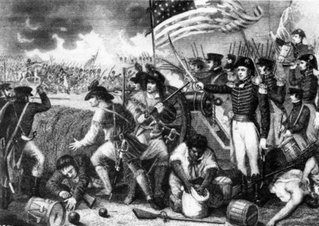

He wasn’t president of anything yet, and he was having a hard go of leading an army in rebellion against the might of the British Crown. But on the day after Christmas, 1776, George Washington famously commanded a sucker-punch surprise attack on a Hessian force at Trenton, NJ, capturing more than 800 of the surprised Germans while hardly losing a man.

Less well known is the Battle of Princeton, fought on January 3, 1777. (The pictured plaque at Princeton Battlefield State Park in New Jersey says: "Route of Washington's march by night from Trenton to Princeton and Victory, January 3, 1777.") The Battle of Trenton, though an immense psychological victory for the rebels, hardly settled matters in New Jersey. There had to be a follow-up battle, and, taking the initiative again, Washington decided to attack the British garrison at Princeton.

“It was a tremendously risky plan,” wrote Thomas Fleming in 1776: Year of Illusions (1975). “Washington was placing his entire army between two British armies, one commanded by Howe in New York, the other by Cornwallis in Trenton… but it had its advantages, too. Foremost… as Washington put it later, [was] “that it would avoid the appearance of a retreat.”

The Battle of Princeton was a bloody see-saw affair, with Washington himself in the line of fire part of the time. He was unhurt, and eventually the Americans prevailed, with some of the British regulars retreating intact, and others fleeing in disorder. Afterwards, some of the Americans looted the town of Princeton -- pay, after all, was pretty bad in the Colonial army.

According to Fleming, “Cornwallis had yielded to panic and marched his army all night from Princeton to New Brunswick… when no American attack [on New Brunswick] was forthcoming, it dawned on most members of the British army that they had been outfought, outgeneraled, and – worst of all – made to look ridiculous.

“Even more devastating was the impact of Washington’s success on the loyalists of New Jersey. The British high command… formed a defensive line along the Raritan River, with heavy concentrations of troops in Perth Amboy and New Brunswick. Elsewhere in the state, American rebels were in charge. Loyalists were arrested, imprisoned, and fined…”